Leicester’s Roman inhabitants lived in a wide variety of houses, ranging from rows of small, simple rectangular buildings built along street fronts (with domestic rooms located behind shops or workshops) to larger, elaborate townhouses built around colonnaded courtyards.

- The Jewry Wall is one of the largest remaining Roman masonry structures in Britain

- Kathleen Kenyon is one of the greatest archaeologists of the 20th century. She also made ground-breaking discoveries at Jericho and Jerusalem in the Middle East

- No one really knows how the Jewry Wall got its name. It may have come from the latin janua (gateway) or medieval jurat (juror)

The social centre of Roman Leicester

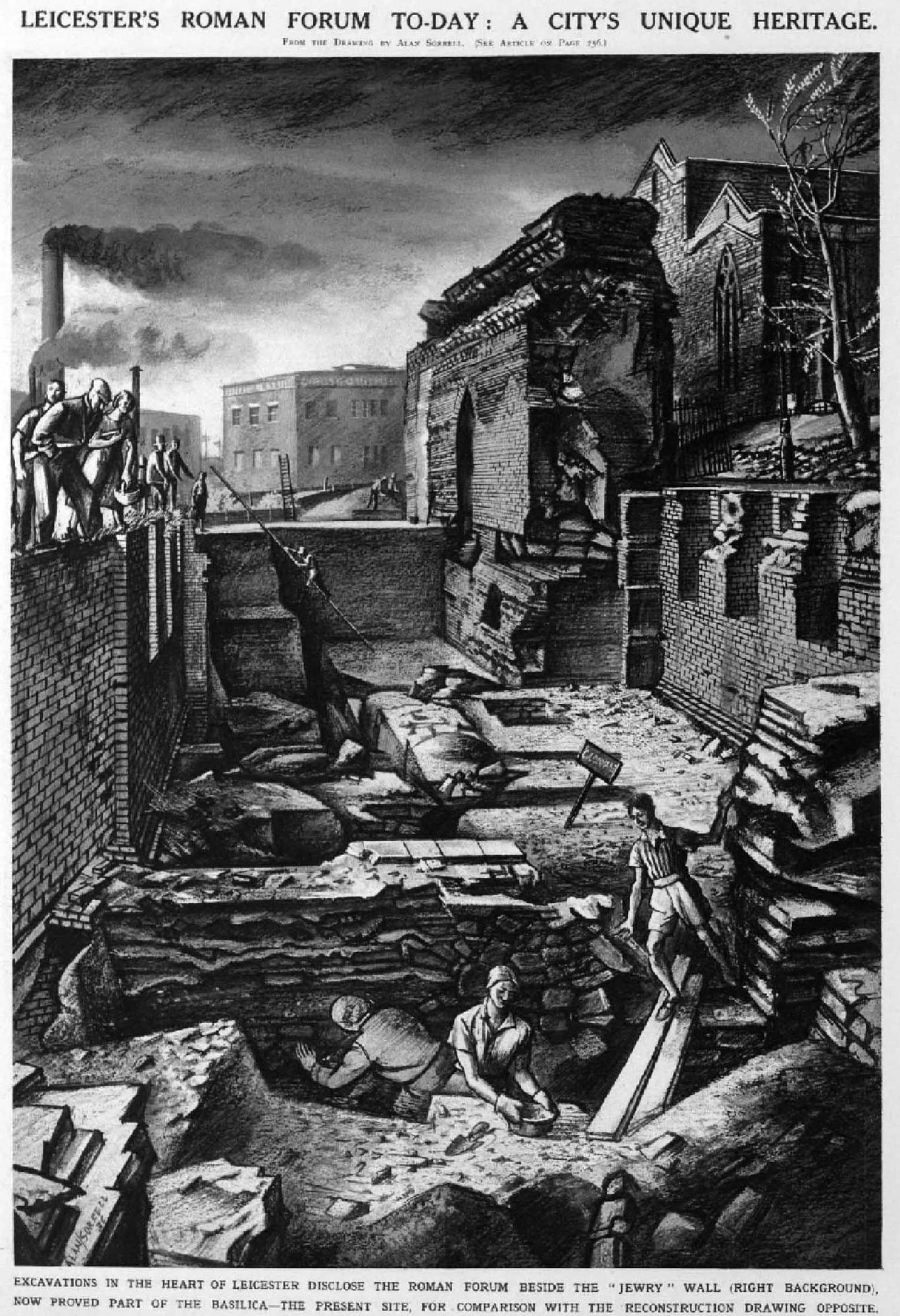

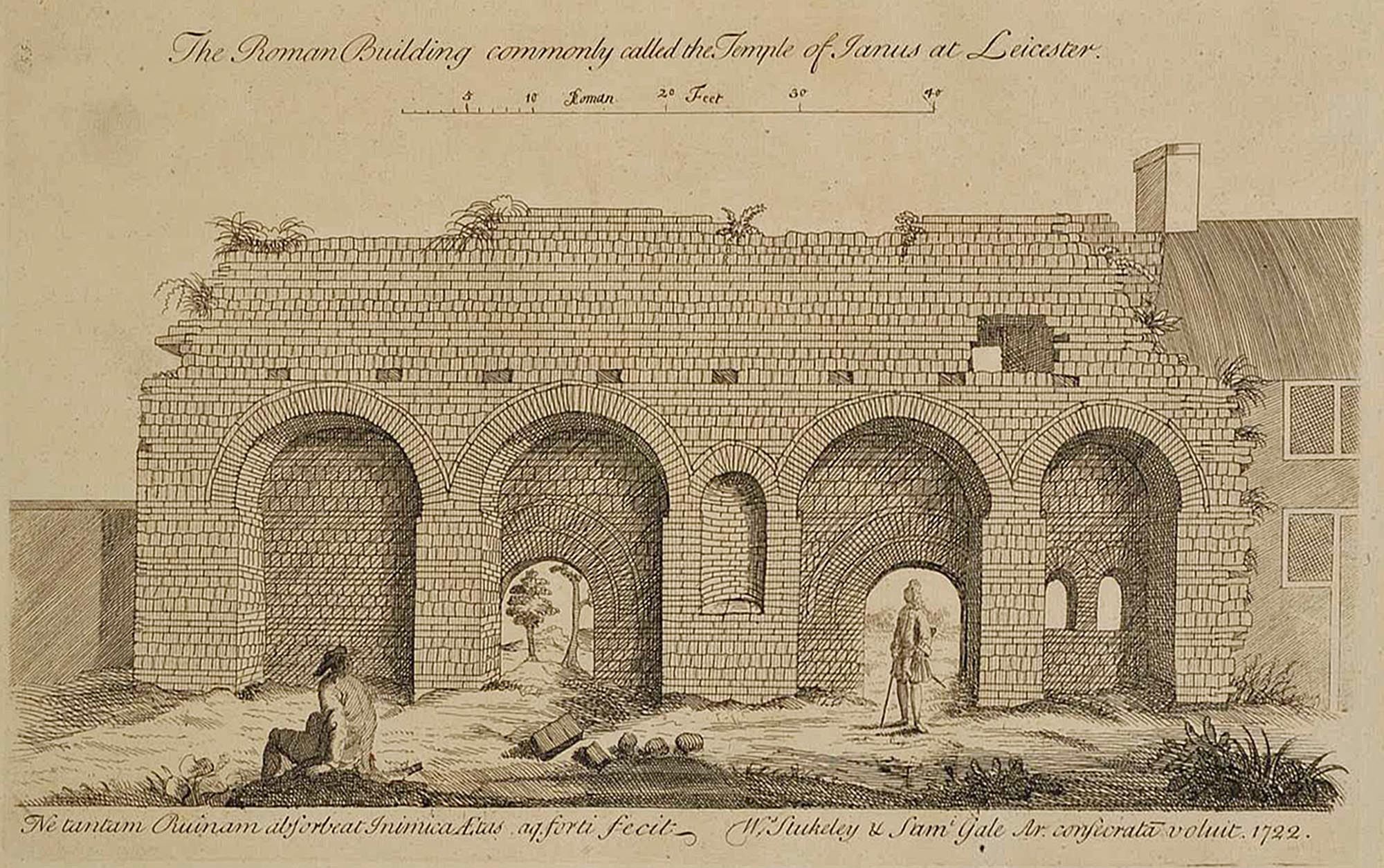

Today, the only visible reminder of Leicester’s Roman past, in-situ, is the Jewry Wall. At 23m long, 9m high and 2.5m thick, it is one of the largest pieces of Roman masonry still standing in Britain. Since the medieval period, when it was commonly believed to be part of a Temple to Janus, there has been much discussion about what the Jewry Wall may have been. It was not until it was excavated in the late 1930s by the pioneering archaeologist Dame Kathleen Kenyon (coincidentally in preparation for the building of a new swimming baths) that its role as part of a substantial bathing complex was demonstrated, and not the town’s forum as previously thought. Kenyon’s excavations were the first large-scale archaeological investigation of Roman Leicester and paved the way for eighty years of archaeological discoveries.

Not just a place to bath…

Bathing was an integral part of cultural and social life in Roman towns regardless of who you were. Bath-houses were not just places to get clean: customers would also exercise, relax, eat, socialise and conduct business. They would now be considered similar to community centres, combining all the facilities provided by gyms, spas, libraries, shopping centres and restaurants.

How to bathe, Roman style

Built in the mid-2nd century CE, the bath complex did not change much and probably remained in use until the 4th century. Access to the baths is thought to have been through arches in the Jewry Wall. This was the west wall of a large, aisled basilica on the eastern side of the complex, most of which now lies beneath the Church of St Nicholas. This was the palaestra, the exercise hall where men could meet, box, wrestle and play ball games.

The central focus of the baths themselves was the tepidarium, the warm room heated from under the floor through a hypocaust, where bathers could assemble and relax before moving on to the hot or cold baths – the caldaria or the frigidarium. Bathers would cover themselves with oils and use a tool called a strigil to scrape off the dirt and oil. The hot rooms were maintained at a temperature of about forty degrees centigrade – this made them very humid, much like a modern sauna. The final step was to plunge into a pool of cold water, to close the pores and refresh the body.

The stage is set…

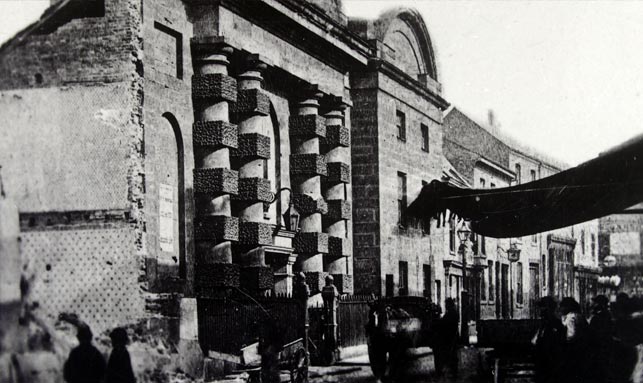

Bathing was not the only way to relax in Roman Leicester. Recent archaeological excavation on the corner of Highcross Street and Vaughan Way found parts of a substantial Roman public building, most likely the supports for the curved seating of a theatre, built in the early 3rd century behind the town’s macellum (market hall).

Other entertainments

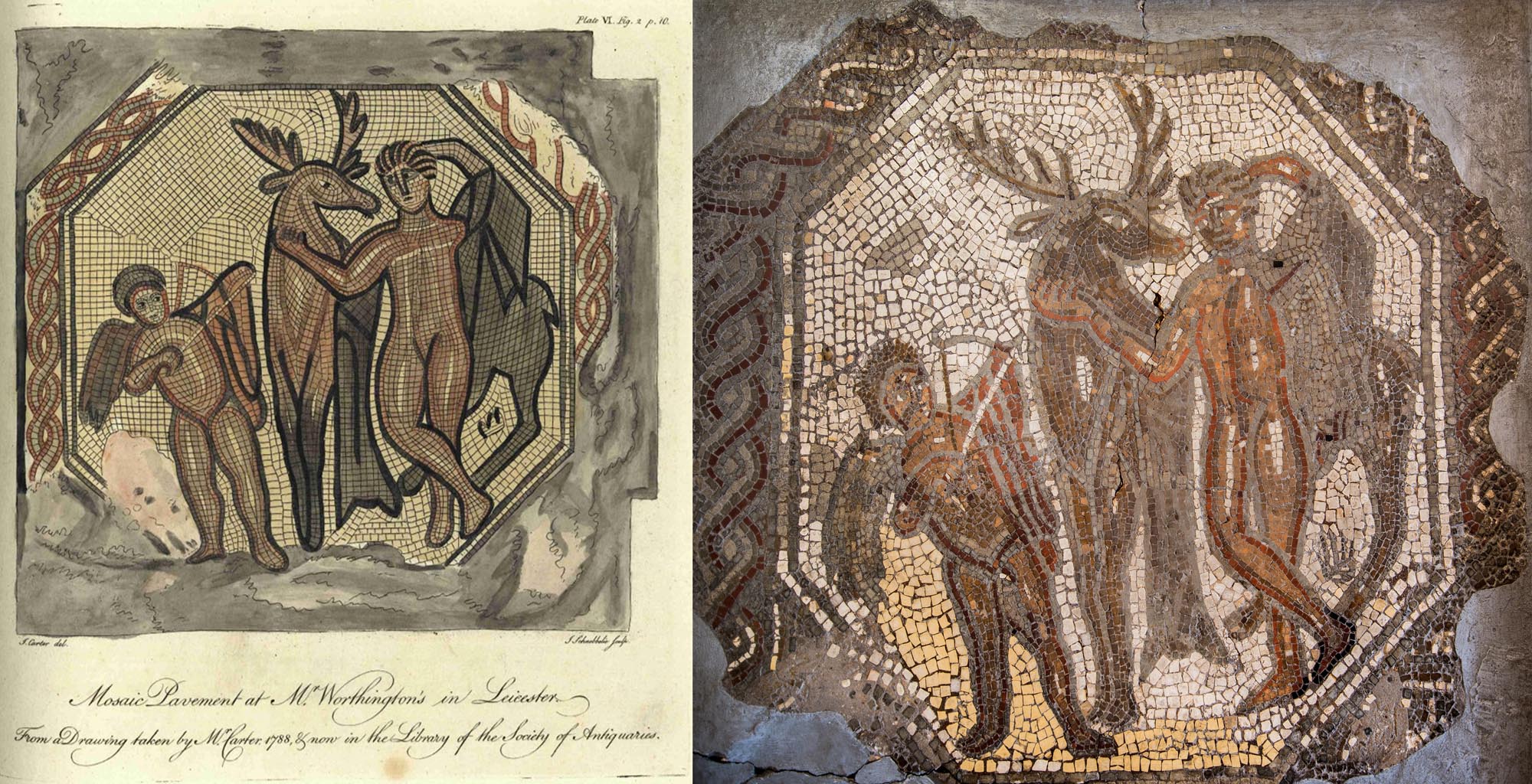

Traces of other public entertainments and Roman culture enjoyed by Leicester’s populace have been found on other sites, including a small graffitied sherd of pottery bearing the names Verecunda the actress (or female gladiator) and Lucius the gladiator, and a mosaic depicting the story of Cyparissus from Ovid’s poem Metamorphoses.

Gallery

Mike Codd / Leicester Arts and Museums Service

A. Sorrell, London Illustrated News 1930s

Stuckley’s Itinerarium Curiosum

University of Leicester Archaeological Services

The Romans in Leicester

Roman Leicester

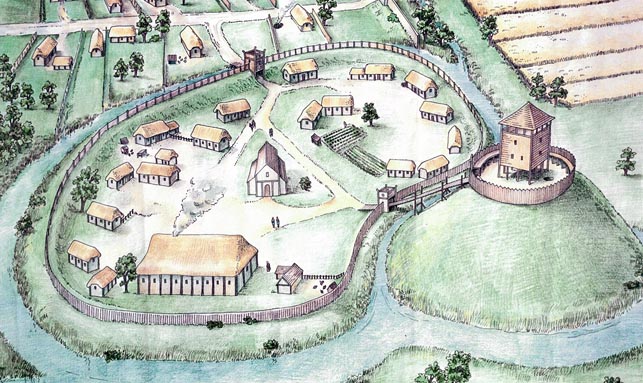

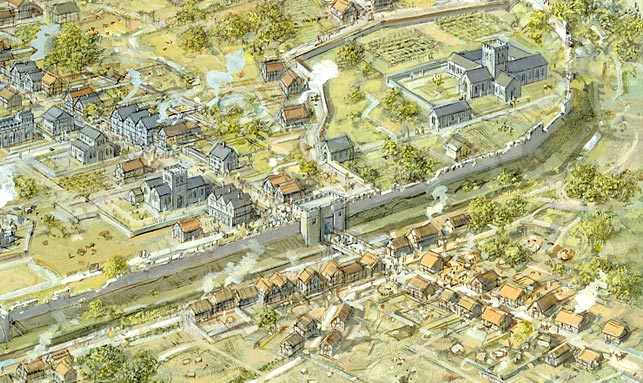

(47- 500) A military fort was erected, attracting traders and a growing civilian community to Leicester (known as Ratae Corieltauvorum to the Romans). The town steadily grew throughout the reign of the Romans.

Medieval Leicester

(500 – 1500) The early years of this period was one of unrest with Saxon, Danes and Norman invaders having their influences over the town. Later, of course, came Richard III and the final battle of the Wars of the Roses was fought on Leicester’s doorstep.

-

The Castle Motte1068

-

Leicester Cathedral1086

-

St Mary de Castro1107

-

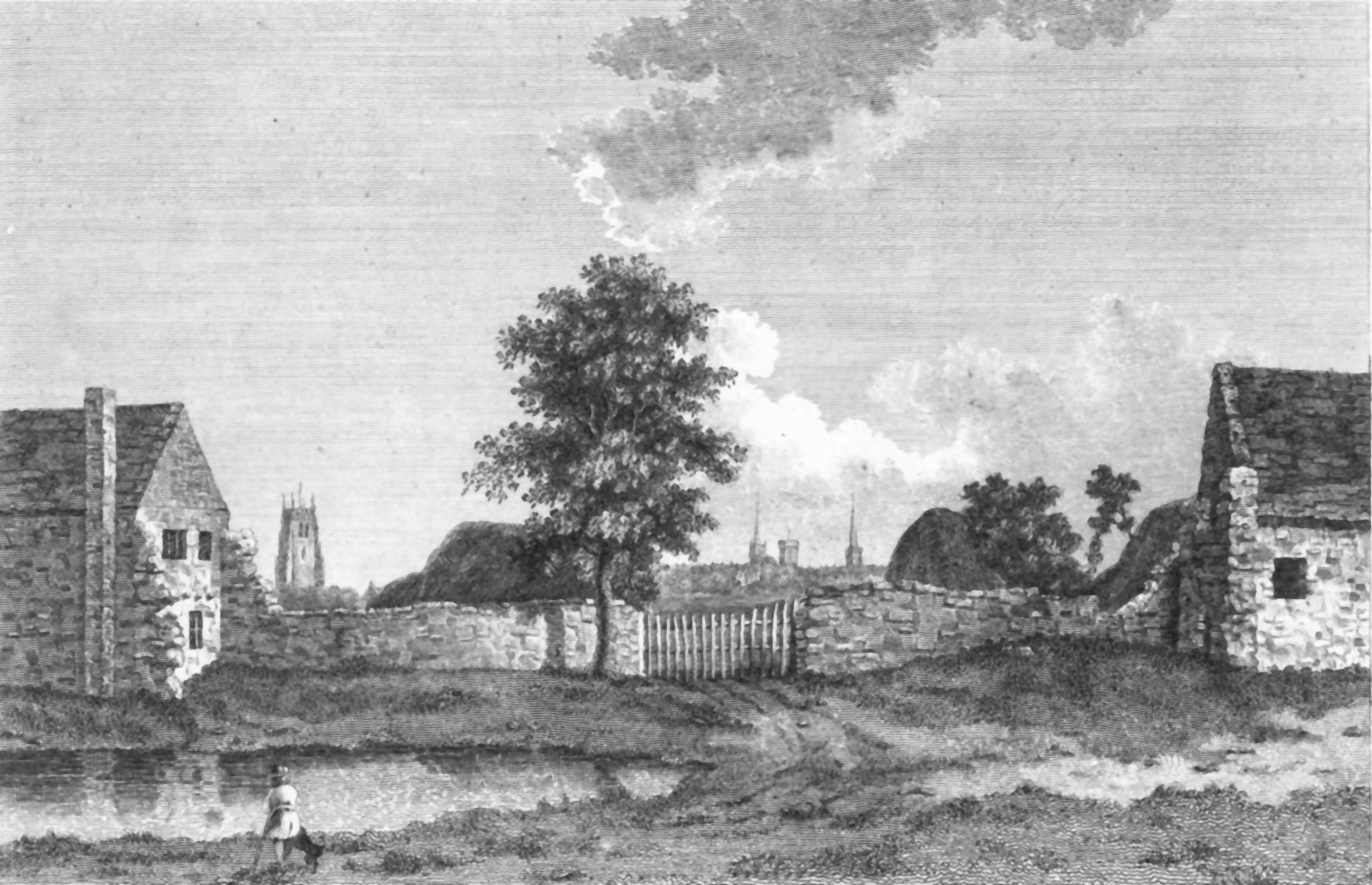

Leicester Abbey1138

-

Leicester Castle1150

-

Grey Friars1231

-

The Streets of Medieval Leicester1265

-

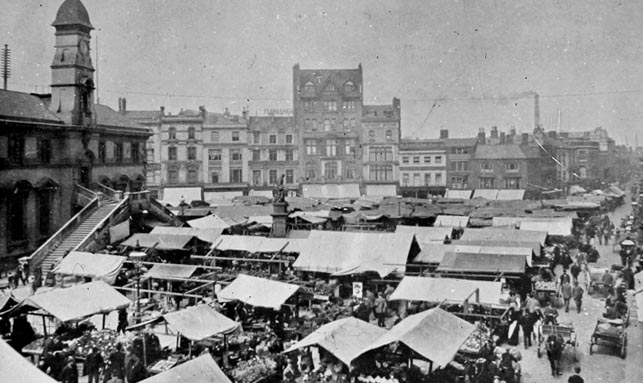

Leicester Market1298

-

Trinity Hospital and Chapel1330

-

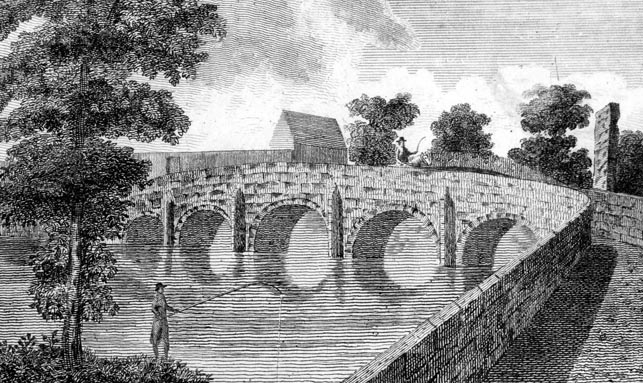

Bow Bridgecirca 1350

-

Church of the Annunciation1353

-

John O’Gaunt’s Cellar1361

-

St John's Stone1381

-

Leicester Guildhall1390

-

The Magazine1400

-

The Blue Boar Inn1400

-

The High Cross1577

Tudor & Stuart Leicester

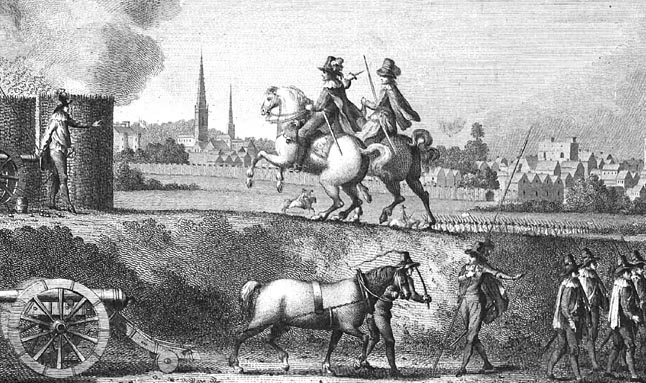

(1500 – 1700) The wool trade flourished in Leicester with one local, a former mayor named William Wigston, making his fortune. During the English Civil War a bloody battle was fought as the forces of King Charles I laid siege to the town.

Georgian Leicester

(1700 – 1837) The knitting industry had really stared to take hold and Leicester was fast becoming the main centre of hosiery manufacture in Britain. This new prosperity was reflected throughout the town with broader, paved streets lined with elegant brick buildings and genteel residences.

-

Great Meeting Unitarian Chapel1708

-

The Globe1720

-

17 Friar Lane1759

-

Black Annis and Dane Hills1764

-

Leicester Royal Infirmary1771

-

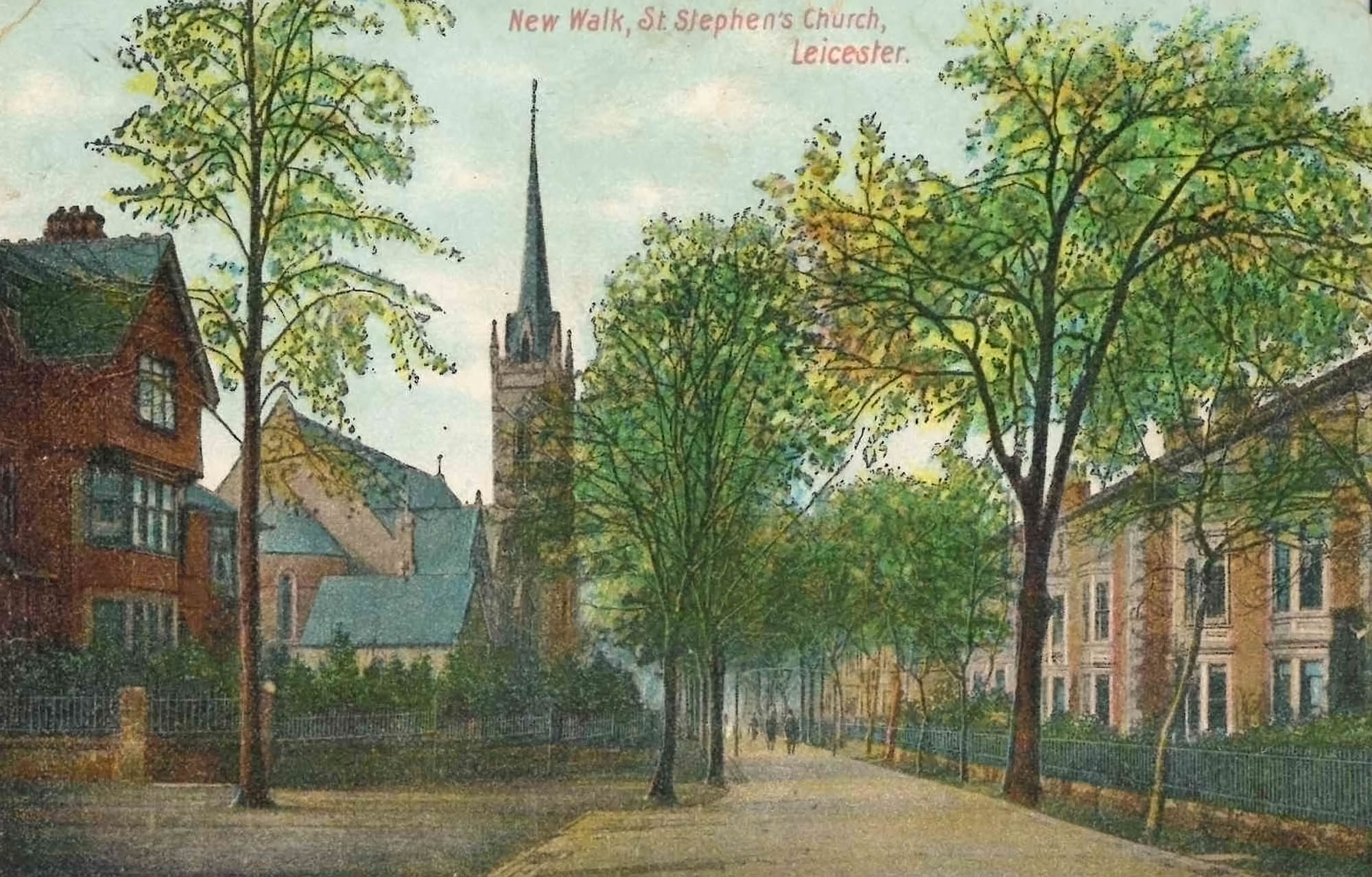

New Walk1785

-

Freemasons’ Hall1790

-

Gaols in the City1791

-

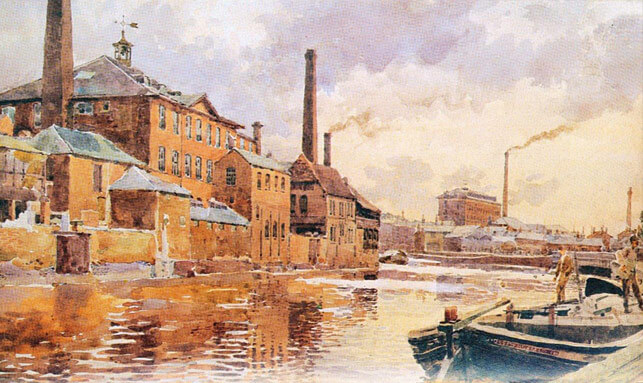

Friars Mill1794

-

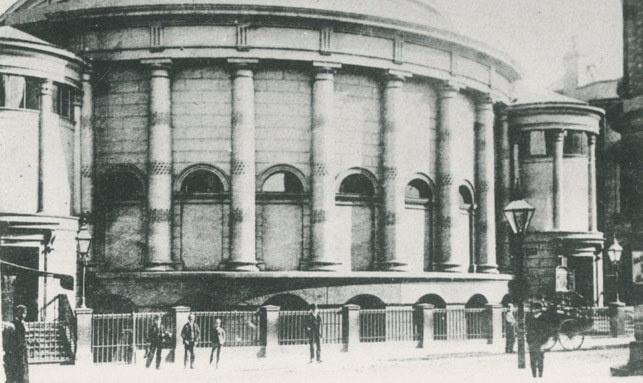

City Rooms1800

-

Development of Highfields1800

-

Wesleyan Chapel1815

-

20 Glebe Street1820

-

Charles Street Baptist Chapel1830

-

Glenfield Tunnel1832

-

James Cook1832

Victorian Leicester

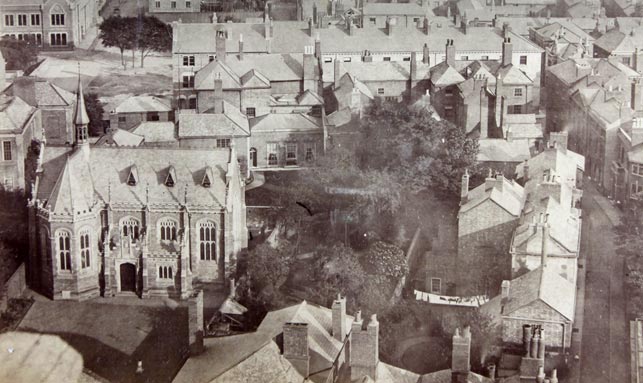

(1837 – 1901) The industrial revolution had a huge effect on Leicester resulting in the population growing from 40,000 to 212,000 during this period. Many of Leicester's most iconic buildings were erected during this time as wealthy Victorians made their mark on the town.

-

Leicester Union Workhouse1839

-

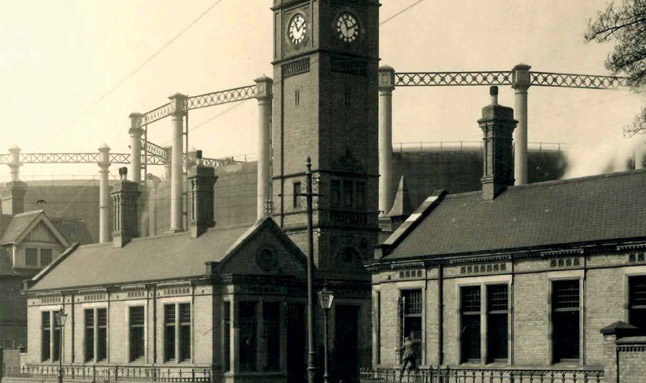

Campbell Street and London Road Railway Stations1840

-

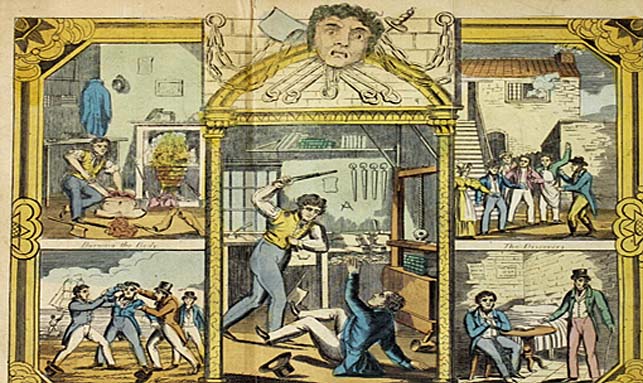

The Vulcan Works1842

-

Belvoir Street Chapel1845

-

Welford Road Cemetery1849

-

Leicester Museum & Art Gallery1849

-

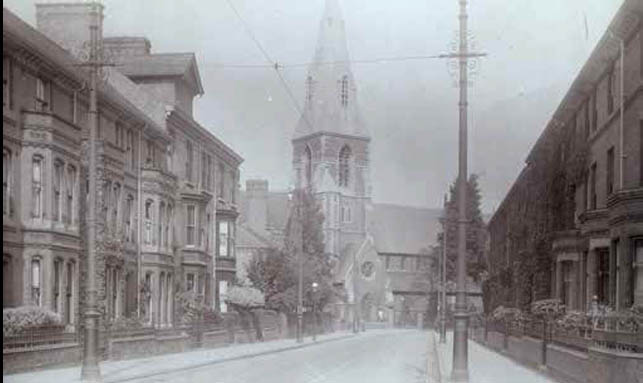

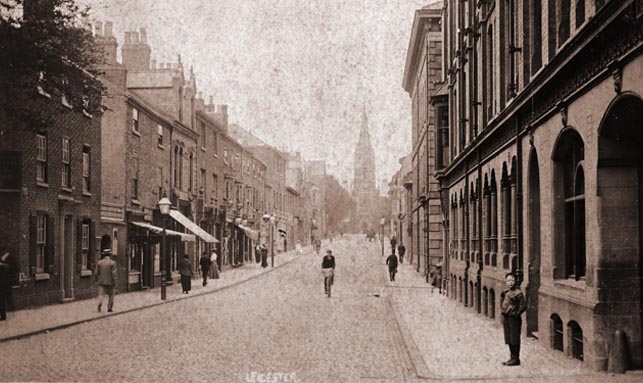

King Street1850

-

Cook’s Temperance Hall & Hotel1853

-

Amos Sherriff1856

-

Weighbridge Toll Collector’s House1860

-

4 Belmont Villas1862

-

Top Hat Terrace1864

-

Corah and Sons - St Margaret's Works1865

-

Kirby & West Dairy1865

-

The Clock Tower1868

-

Wimbledon Works1870

-

The Leicestershire Banking Company1871

-

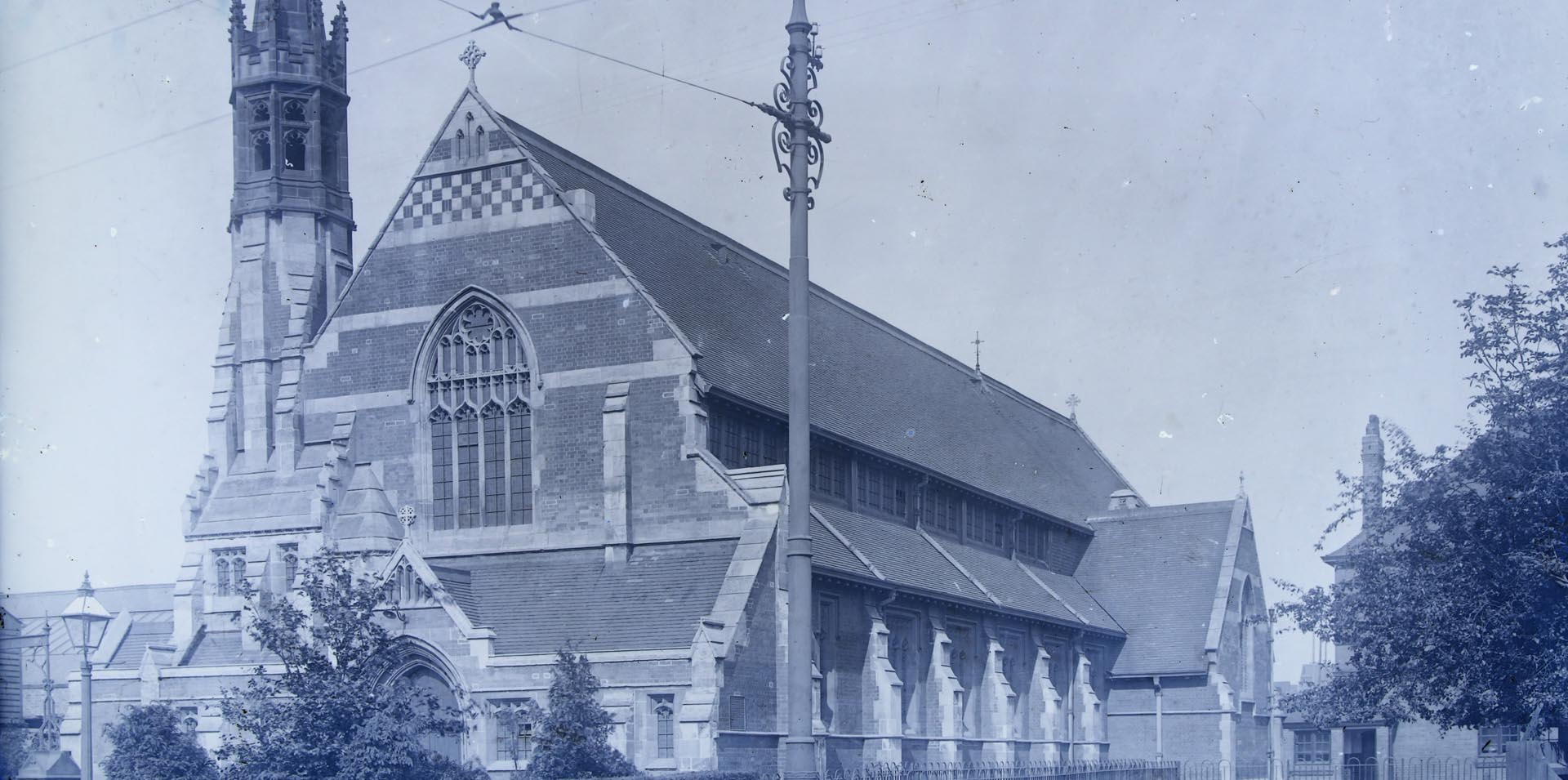

St Mark’s Church and School1872

-

Victorian Turkish Baths1872

-

The Town Hall1876

-

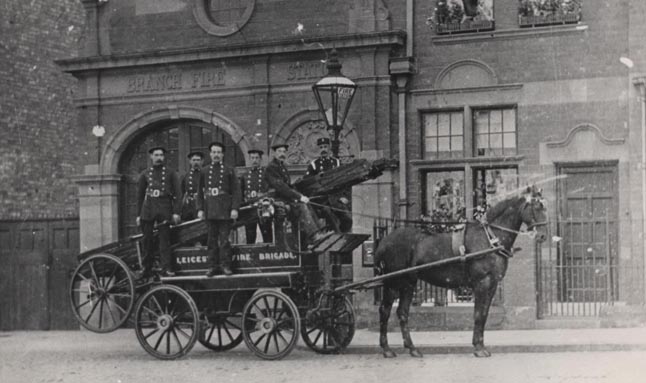

Central Fire Stations1876

-

Aylestone Road Gas Works and Gas Museum1879

-

Gas Workers Cottages1879

-

Leicestershire County Cricket Club1879

-

Welford Road Tigers Rugby Club1880

-

Secular Hall1881

-

Development of Highfields1800

-

Abbey Park1881

-

Abbey Park Buildings1881

-

Victoria Park and Lutyens War Memorial1883

-

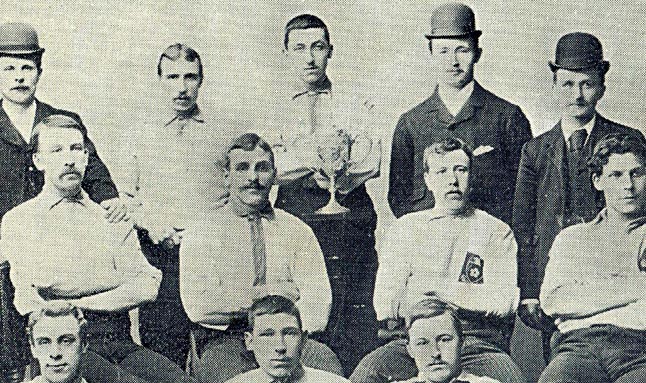

Leicester Fosse FC 18841884

-

Leicester Coffee and Cocoa Company Coffee Houses1885

-

St Barnabas Church and Vicarage1886

-

Abbey Pumping Station1891

-

Luke Turner & Co. Ltd.1893

-

West Bridge Station1893

-

Thomas Cook Building1894

-

The White House1896

-

Alexandra House1897

-

Leicester Boys Club1897

-

Grand Hotel and General Newsroom1898

-

Highfield Street Synagogue1898

-

Western Park1899

-

Asfordby Street Police Station1899

-

Leicester Central Railway Station1899

Edwardian Leicester

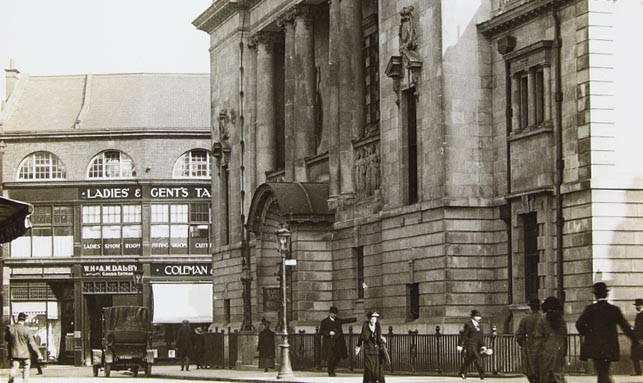

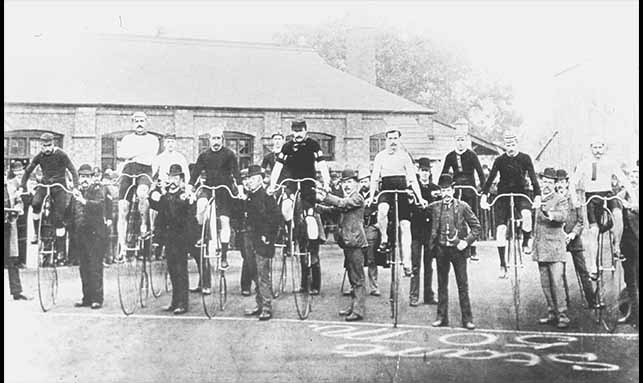

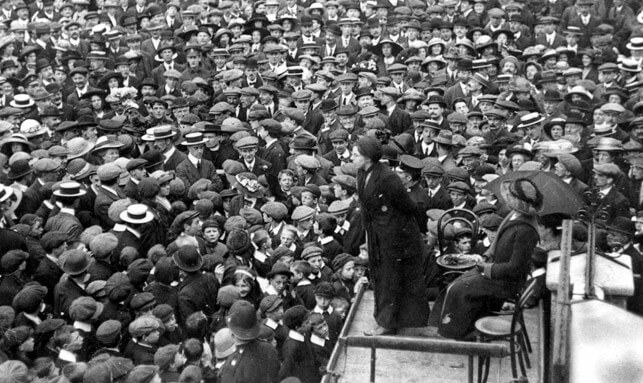

(1901 – 1910) Electric trams came to the streets of Leicester and increased literacy among the citizens led to many becoming politicised. The famous 1905 ‘March of the Unemployed to London’ left from Leicester market when 30,000 people came to witness the historic event.

-

YMCA Building1900

-

The Palace Theatre1901

-

Pares's Bank1901

-

Coronation Buildings1902

-

Halfords1902

-

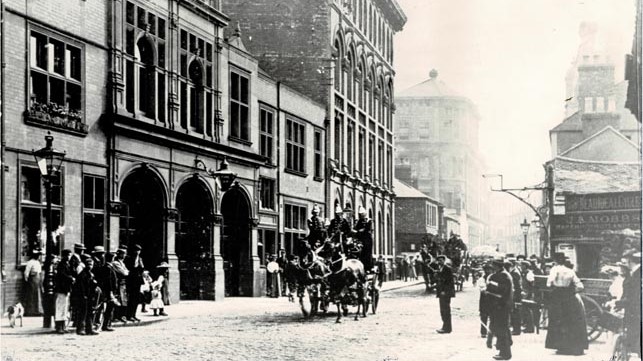

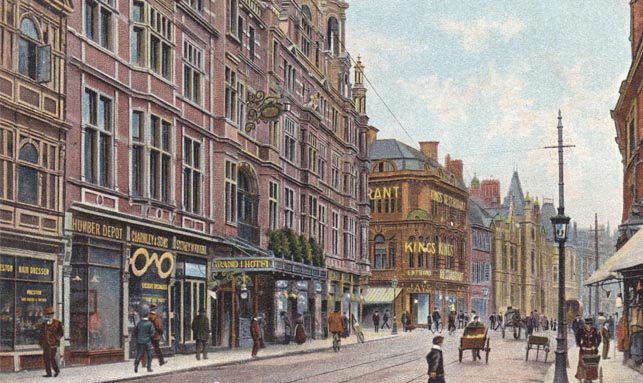

High Street1904

-

George Biddles and Leicester's Boxing Heritage1904

-

Municipal Library1905

-

Leicester Boys Club1897

-

The Marquis Wellington1907

-

Guild Hall Colton Street1909

-

Women's Social and Political Union Shop1910

-

Turkey Café1901

Early 20th Century Leicester

(1910 – 1973) The diverse industrial base meant Leicester was able to cope with the economic challenges of the 1920s and 1930s. New light engineering businesses, such as typewriter and scientific instrument making, complemented the more traditional industries of hosiery and footwear manufacturing.

-

Dryad Handicrafts1912

-

De Montfort Hall1913

-

Leicester During the First World War1914

-

Fox’s Glacier Mints1918

-

Statue of Liberty1919

-

Housing in Saffron Lane1924

-

Winstanley House1925

-

Housing in North Braunstone1926

-

Lancaster Road Fire Station1927

-

The Little Theatre1930

-

Saffron Hill Cemetery1931

-

Braunstone Hall Junior School1932

-

Former City Police Headquarters1933

-

Savoy Cinema1937

-

Eliane Sophie Plewman1937

-

City Hall1938

-

Athena - The Odeon Cinema1938

-

The Blitz in Highfields1940

-

Freeman, Hardy and Willis - Leicester Blitz1940

-

Leicester Airport1942

-

Leicester’s Windrush Generations1948

-

Netherhall Estate1950

-

Housing at Eyres Monsell1951

-

Silver Street and The Lanes1960

-

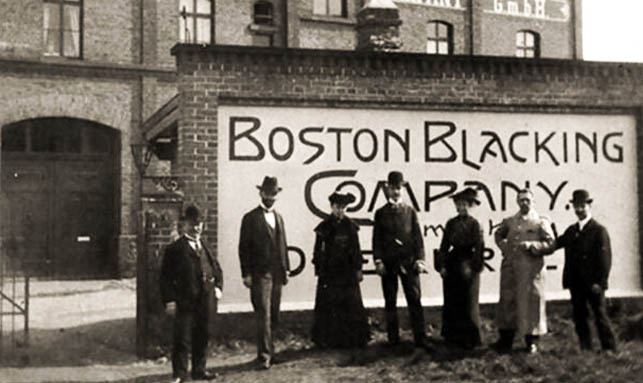

Bostik1960

-

Auto-Magic Car Park (Lee Circle)1961

-

University of Leicester Engineering Building1963

-

Sue Townsend Theatre1963

-

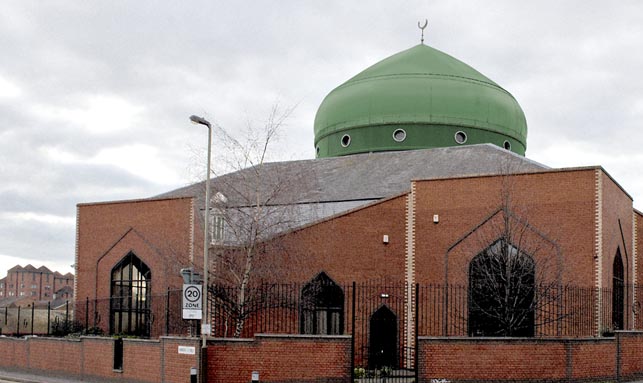

Central Mosque1968

-

Belgrave Flyover1973

Modern Leicester

(1973 – present day) Industry was still thriving in the city during the 1970s, with the work opportunities attracting many immigrants from all over the world. While industry has declined in recent years, excellent transport links have made Leicester an attractive centre for many businesses. The City now has much to be proud of including its sporting achievements and the richness of its cultural heritage and diversity.

-

Haymarket Theatre1973

-

The Golden Mile1974

-

Acting Up Against AIDS1976

-

Belgrave Neighbourhood Centre1977

-

Diwali in Leicester1983

-

Leicester Caribbean Carnival1985

-

Samworth Brothers1986

-

Jain Centre1988

-

Guru Nanak Dev Ji Gurdwara1989

-

King Power Stadium2002

-

LCB Depot2004

-

Curve2008

-

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir2011

-

Makers Yard2012

-

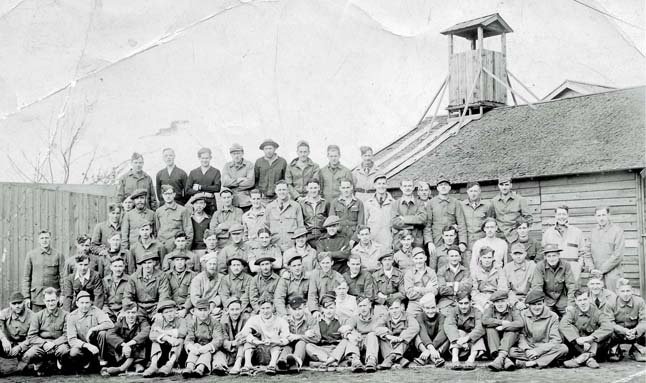

VJ Day 80th Anniversary2020

- Roman Leicester

- Medieval Leicester

- Tudor & Stuart Leicester

- Georgian Leicester

- Victorian Leicester

- Edwardian Leicester

- Early 20th Century Leicester

- Modern Leicester