- The White House in Clarendon Park is one of Leicester’s most distinctive houses and is Grade II listed.

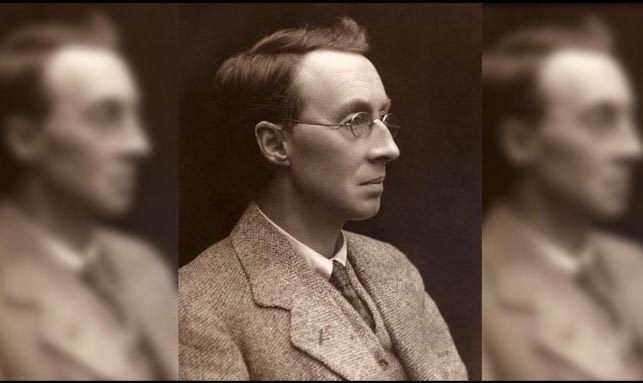

- Arthur Gimson, a successful businessman in his forties, had just become a director of Gimson & Co. in 1896.

- By 1896, after three years in the South Cotswolds, Gimson's admiration for local stone farmhouses influenced The White House's design.

The White House

The White House in Clarendon Park is one of Leicester’s most distinctive houses and is Grade II listed. It was the second villa designed and built by Ernest Gimson in the city’s southern suburbs in 1896 and is a good example of an Arts and Crafts Movement domestic building.

The client and the site

Arthur Gimson, a successful businessman in his forties, had just become a director of Gimson & Co. in 1896. He was a married man; he and his wife Alice already had a large family. He acquired a plot of land on North Avenue, an awkwardly-shaped site but one that was close to the amenities of Victoria Park and the town centre, and asked his half-brother Ernest Gimson to design a house for him. The house had to be placed quite tightly within the narrower part of the plot because of building restrictions. This however allowed for a substantial garden and a tennis court to be fitted into the wider section and inspired Gimson to design the three-sided gable end at an angle to the road. This unusual, dramatic and windowless feature juts out almost like the prow of a ship.

The design and construction

By 1896 Gimson had been living in the south Cotswold countryside for three years and his observation of and admiration for the stone-built farmhouses in local villages influenced the design of The White House. The intention was for the building to be lime-washed annually; this technique was traditionally used in the Cotswolds and elsewhere to disinfect and waterproof the exterior of rural buildings. The house is now painted with masonry paint but it remains white and the beam ends and wire-cut bricks are still visible through the paint. It is this aspect that gave the house its name and ensures that it still stands out from the largely contemporaneous surrounding houses in red brick with mock Tudor detailing.

The garden front features a pair of two-storey bays each with a panel modelled in Keene’s cement, a type of rough-cast plaster (plaster with the addition of gravel) suitable for exterior use, featuring the client’s initials ‘A J G’, a tree and various leaf and fruit sprigs within a diaper pattern designed by Gimson. The work was executed by George Bankart, Gimson’s friend who had trained with him in Isaac Barradale’s architectural office. Bankart went on to specialise in plasterwork but he may well have taken a hands-on role in overseeing the building work in Gimson’s absence. Other decorative features are the lead rainwater hoppers decorated with hearts and flowers which were made to Gimson’s design by a local company, F. W. Haskard & Co. who were based in St George’s Buildings, Halford Street, Leicester. The firm obviously hoped that Gimson’s designs would bring them additional work as they produced postcards that feature photographs of the cast lead hoppers and pipework.i There is no evidence however of these designs being used elsewhere.

The interior

The interior layout of The White House was not typical of the late 19th century. The accepted norm was for the drawing room to face the afternoon sun to the south and west and the kitchen to face the north or east. The tight plot made this impossible – instead the drawing room looks out towards the entrance path while the dining and breakfast rooms look north onto the garden and tennis court. Another unconventional feature was that one had to walk through the dining room to gain access to the drawing room. This followed the medieval plan of passing from one reception room into another without a corridor, a tradition which had been revived by Gimson’s friend and mentor Philip Webb in his design of Red House in Bexleyheath, Kent for William Morris in 1856. This obviously proved awkward for a family home where a lot of entertaining took place and in 1900 Arthur Gimson submitted a plan that was accepted to add a corridor and relocate the entrance. A coal house was also added in 1902 by the Leicester architect Arthur H. Hallam.

Inside The White House Gimson designed plaster ceilings and friezes in the dining and drawing rooms which he himself executed with Bankart’s help. One of the most attractive features is the wooden staircase, designed by Gimson and executed by Richard Harrison, the wheelwright in the village of Sapperton nearby Gimson’s Cotswold home. This is an early example of the use of handwork in Gimson’s architecture – the grain of the wood is clearly visible and the uprights and balustrade are attractively chamfered with a draw knife – all features of country woodworking. Otherwise the overall interior was very plain, with wooden floors, simple stone fire surrounds and in the drawing room, austere wood panelling with curtains by Morris & Co. Arthur Gimson subsequently bought some furniture from Gimson and his friend Sidney Barnsley for the house but it was by no means exclusively furnished with Arts and Crafts pieces.

The occupants of The White House

Arthur Gimson’s family – husband and wife and five children – had three live-in servants according to the census in 1901. Christopher Gimson, one of Arthur and Alice’s sons, was over six-foot tall and in about 1904-6, when he was nearly 20 years old, they commissioned an extra-long single bed for him from Ernest Gimson. The bed was made in Gimson’s Daneway Workshops near Cirencester and remained in The White House until 1988 when the then owner, the architect Douglas Smith, donated it to Leicester Museums (D2 1988). By the early 1920s The White House was owned by the Leicester stockbroker C. Victor Smith. He was particularly keen on the style of Arts and Crafts furniture developed by Gimson who had died in 1919 and he commissioned a number of pieces from Gimson’s friend Sidney Barnsley, Sidney’s son Edward whose workshop was at Froxfield, near Petersfield in Hampshire, and Gimson’s former foreman Peter Waals who established his own workshop at Chalford, Gloucestershire after Gimson’s death. Some of these pieces were subsequently acquired by the local hosiery manufacturer Sidney Pick and then donated to Leicester Museums (Oak sideboard by Sidney Barnsley 114.1974, oak dining table by Peter Waals 115.1974).

Gallery

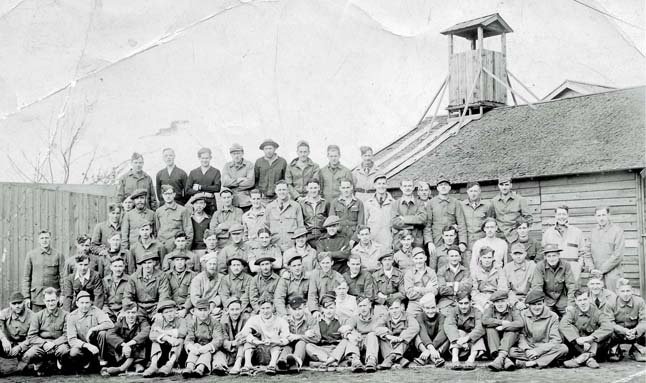

Leicestershire County Council, from the Leicester Evening Mail Photography Collection. Archived under "The White House, Scraptoft Lane," available via Image Leicestershire.

Leicester Mercury / Chris Gordon.

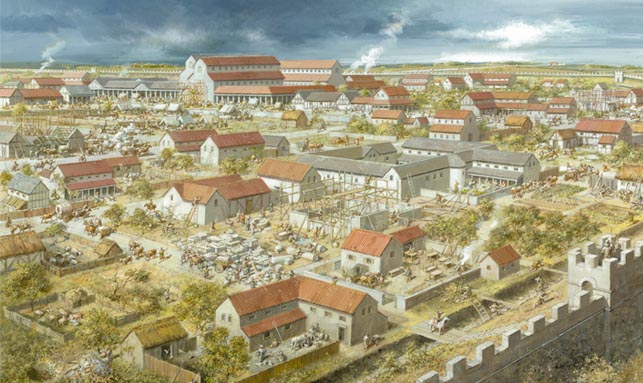

Roman Leicester

(47- 500) A military fort was erected, attracting traders and a growing civilian community to Leicester (known as Ratae Corieltauvorum to the Romans). The town steadily grew throughout the reign of the Romans.

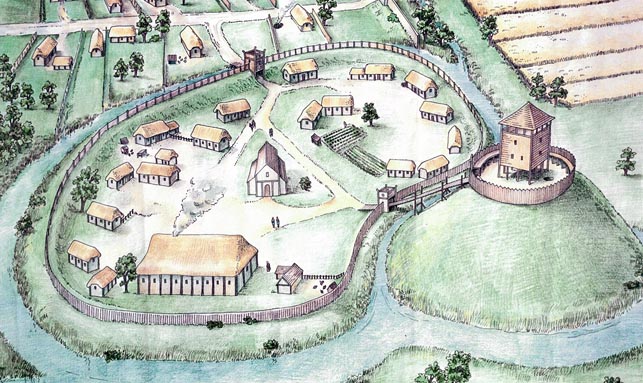

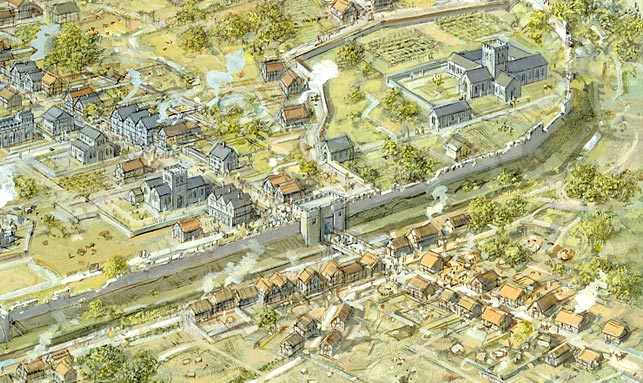

Medieval Leicester

(500 – 1500) The early years of this period was one of unrest with Saxon, Danes and Norman invaders having their influences over the town. Later, of course, came Richard III and the final battle of the Wars of the Roses was fought on Leicester’s doorstep.

-

The Castle Motte1068

-

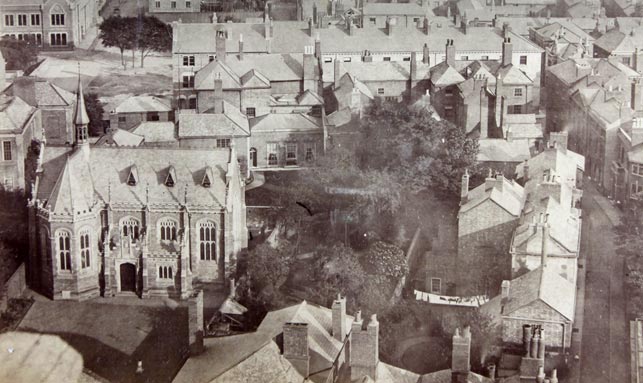

Leicester Cathedral1086

-

St Mary de Castro1107

-

Leicester Abbey1138

-

Leicester Castle1150

-

Grey Friars1231

-

The Streets of Medieval Leicester1265

-

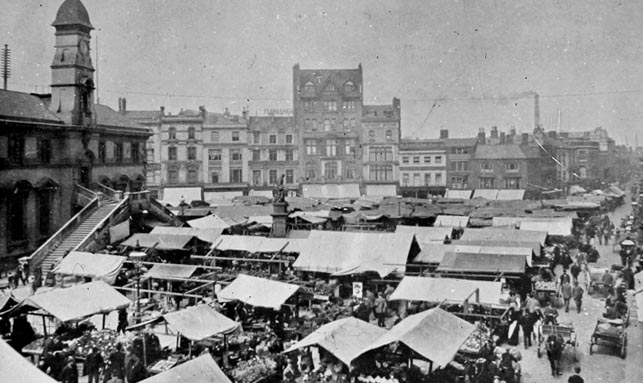

Leicester Market1298

-

Trinity Hospital and Chapel1330

-

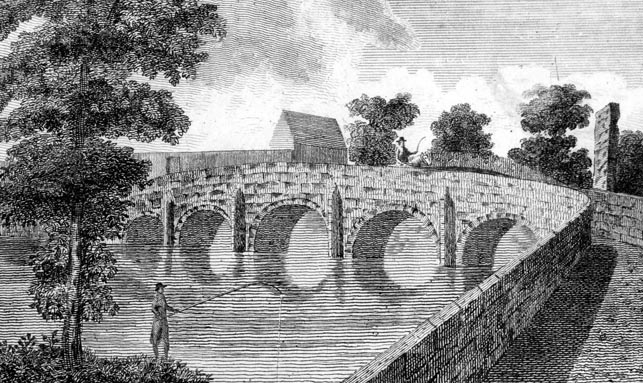

Bow Bridgecirca 1350

-

Church of the Annunciation1353

-

John O’Gaunt’s Cellar1361

-

St John's Stone1381

-

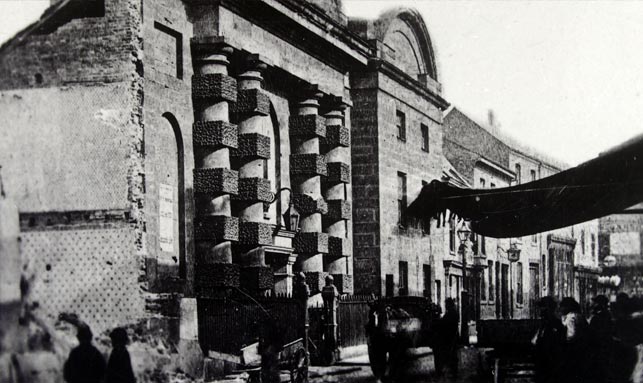

Leicester Guildhall1390

-

The Magazine1400

-

The Blue Boar Inn1400

-

The High Cross1577

Tudor & Stuart Leicester

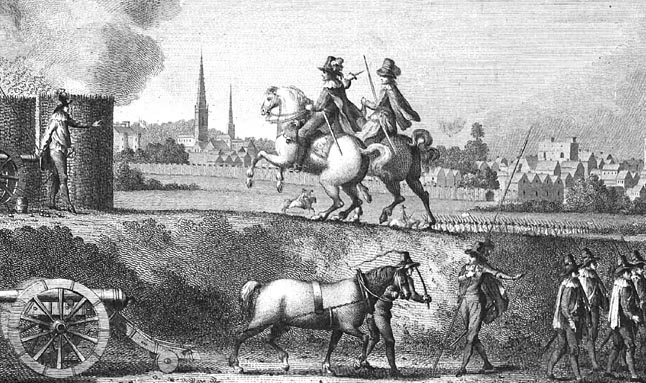

(1500 – 1700) The wool trade flourished in Leicester with one local, a former mayor named William Wigston, making his fortune. During the English Civil War a bloody battle was fought as the forces of King Charles I laid siege to the town.

Georgian Leicester

(1700 – 1837) The knitting industry had really stared to take hold and Leicester was fast becoming the main centre of hosiery manufacture in Britain. This new prosperity was reflected throughout the town with broader, paved streets lined with elegant brick buildings and genteel residences.

-

Great Meeting Unitarian Chapel1708

-

The Globe1720

-

17 Friar Lane1759

-

Black Annis and Dane Hills1764

-

Leicester Royal Infirmary1771

-

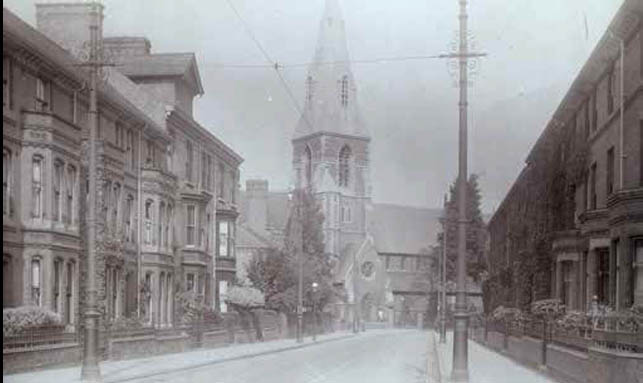

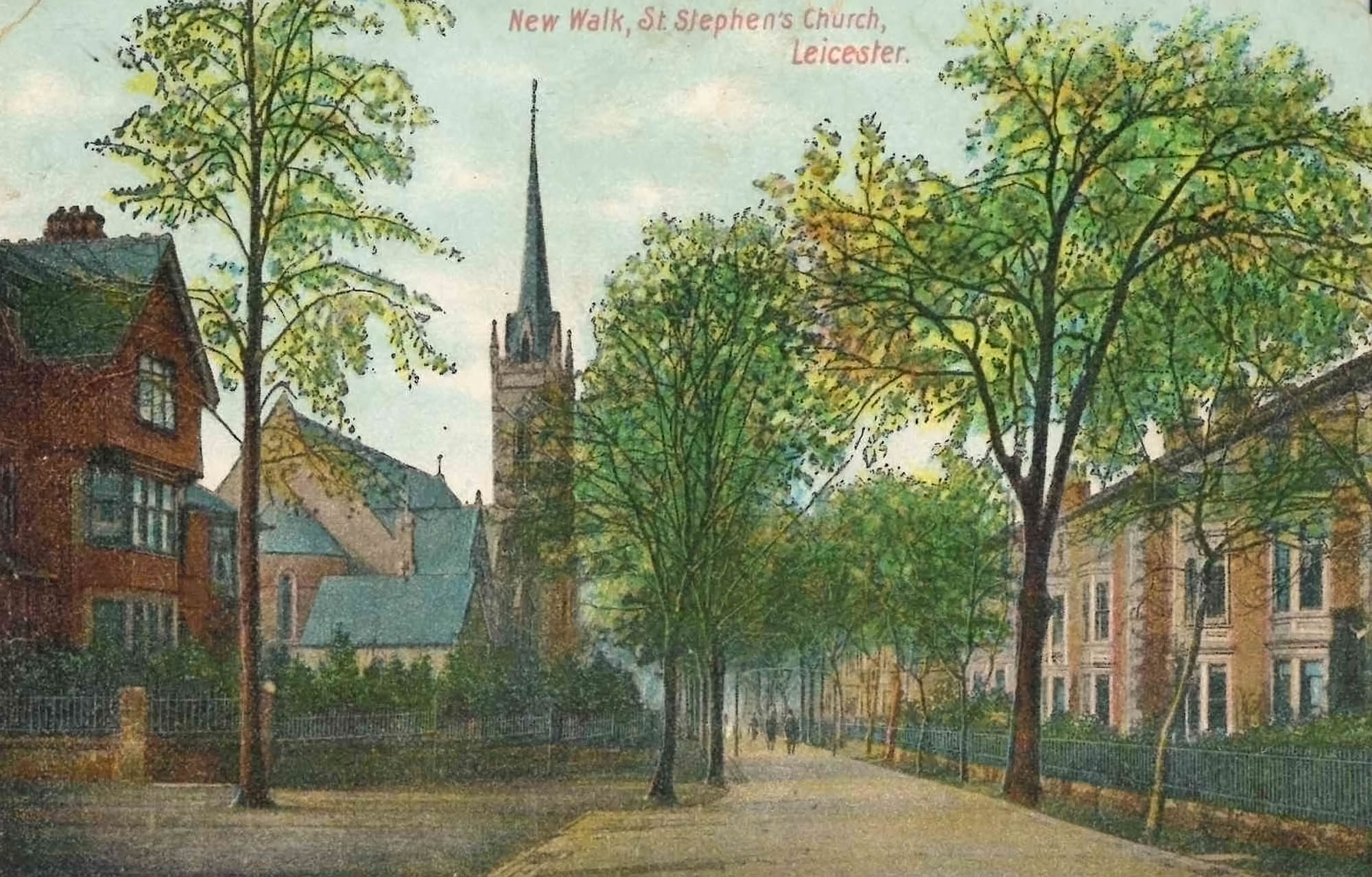

New Walk1785

-

Freemasons’ Hall1790

-

Gaols in the City1791

-

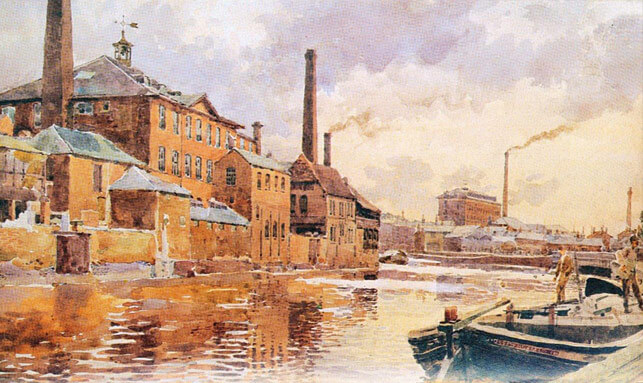

Friars Mill1794

-

City Rooms1800

-

Development of Highfields1800

-

Wesleyan Chapel1815

-

20 Glebe Street1820

-

Charles Street Baptist Chapel1830

-

Glenfield Tunnel1832

-

James Cook1832

Victorian Leicester

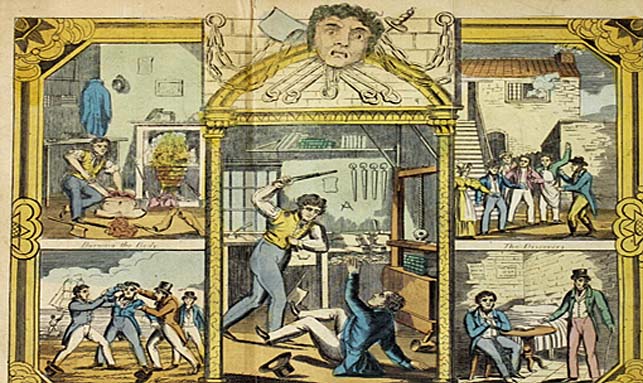

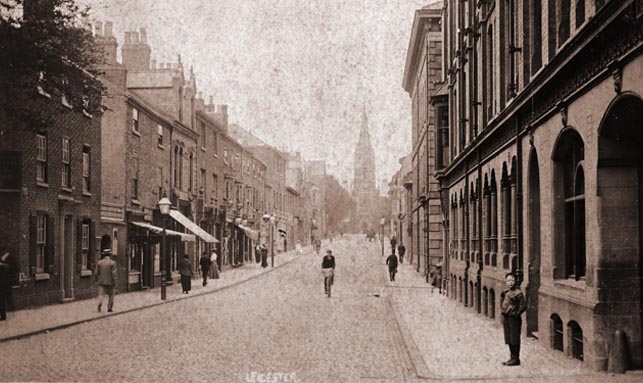

(1837 – 1901) The industrial revolution had a huge effect on Leicester resulting in the population growing from 40,000 to 212,000 during this period. Many of Leicester's most iconic buildings were erected during this time as wealthy Victorians made their mark on the town.

-

Leicester Union Workhouse1839

-

Campbell Street and London Road Railway Stations1840

-

The Vulcan Works1842

-

Belvoir Street Chapel1845

-

Welford Road Cemetery1849

-

Leicester Museum & Art Gallery1849

-

King Street1850

-

Cook’s Temperance Hall & Hotel1853

-

Amos Sherriff1856

-

Weighbridge Toll Collector’s House1860

-

4 Belmont Villas1862

-

Top Hat Terrace1864

-

Corah and Sons - St Margaret's Works1865

-

Kirby & West Dairy1865

-

The Clock Tower1868

-

Wimbledon Works1870

-

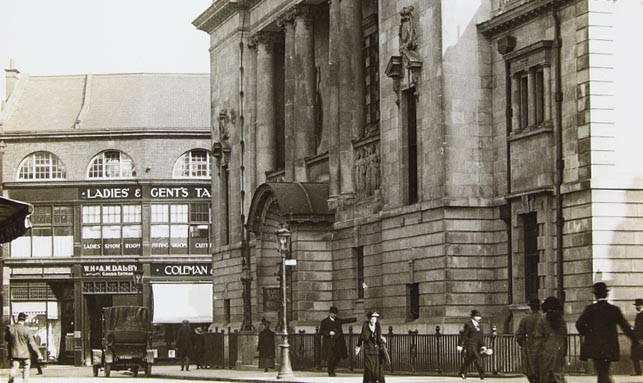

The Leicestershire Banking Company1871

-

St Mark’s Church and School1872

-

Victorian Turkish Baths1872

-

The Town Hall1876

-

Central Fire Stations1876

-

Aylestone Road Gas Works and Gas Museum1879

-

Gas Workers Cottages1879

-

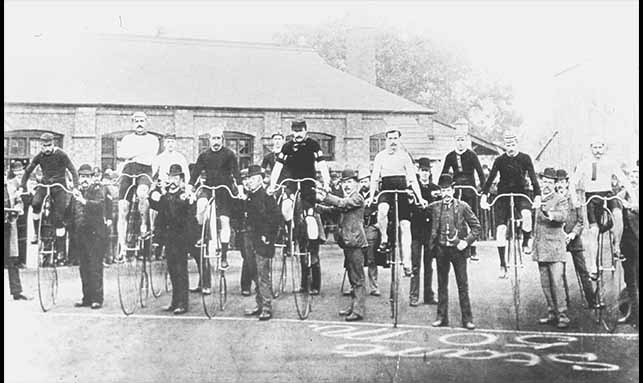

Leicestershire County Cricket Club1879

-

Welford Road Tigers Rugby Club1880

-

Secular Hall1881

-

Development of Highfields1800

-

Abbey Park1881

-

Abbey Park Buildings1881

-

Victoria Park and Lutyens War Memorial1883

-

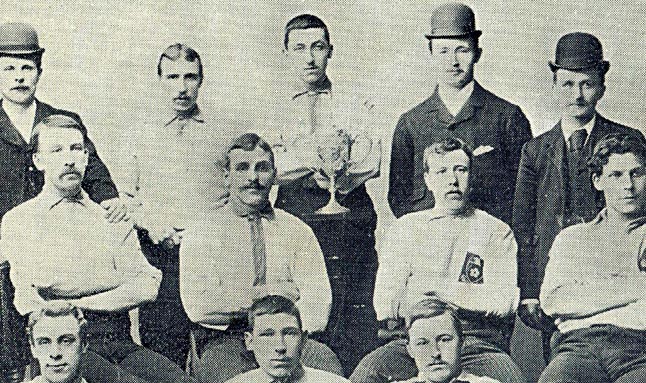

Leicester Fosse FC 18841884

-

Leicester Coffee and Cocoa Company Coffee Houses1885

-

St Barnabas Church and Vicarage1886

-

Abbey Pumping Station1891

-

Luke Turner & Co. Ltd.1893

-

West Bridge Station1893

-

Thomas Cook Building1894

-

The White House1896

-

Alexandra House1897

-

Leicester Boys Club1897

-

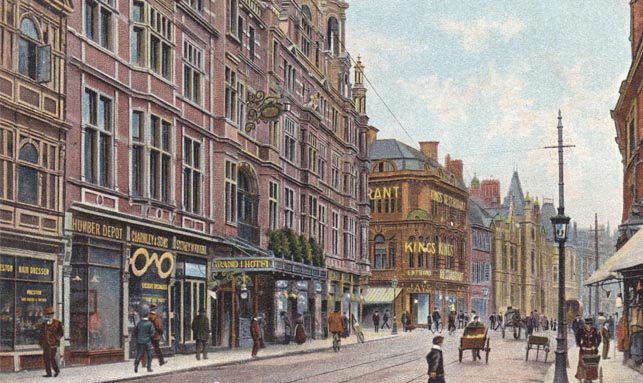

Grand Hotel and General Newsroom1898

-

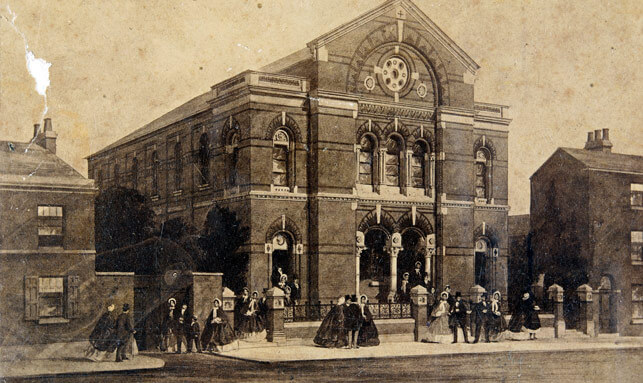

Highfield Street Synagogue1898

-

Western Park1899

-

Asfordby Street Police Station1899

-

Leicester Central Railway Station1899

Edwardian Leicester

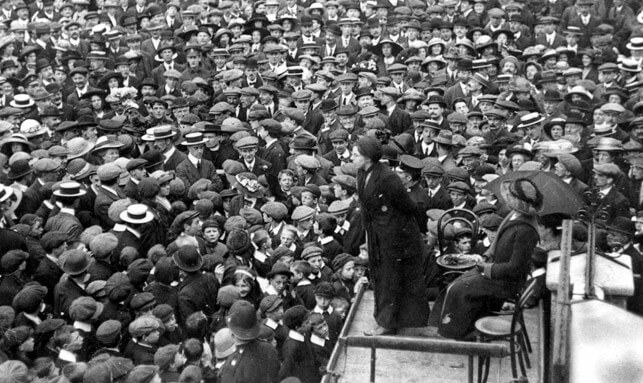

(1901 – 1910) Electric trams came to the streets of Leicester and increased literacy among the citizens led to many becoming politicised. The famous 1905 ‘March of the Unemployed to London’ left from Leicester market when 30,000 people came to witness the historic event.

-

YMCA Building1900

-

The Palace Theatre1901

-

Pares's Bank1901

-

Coronation Buildings1902

-

Halfords1902

-

High Street1904

-

George Biddles and Leicester's Boxing Heritage1904

-

Municipal Library1905

-

Leicester Boys Club1897

-

The Marquis Wellington1907

-

Guild Hall Colton Street1909

-

Women's Social and Political Union Shop1910

-

Turkey Café1901

Early 20th Century Leicester

(1910 – 1973) The diverse industrial base meant Leicester was able to cope with the economic challenges of the 1920s and 1930s. New light engineering businesses, such as typewriter and scientific instrument making, complemented the more traditional industries of hosiery and footwear manufacturing.

-

Dryad Handicrafts1912

-

De Montfort Hall1913

-

Leicester During the First World War1914

-

Fox’s Glacier Mints1918

-

Statue of Liberty1919

-

Housing in Saffron Lane1924

-

Winstanley House1925

-

Housing in North Braunstone1926

-

Lancaster Road Fire Station1927

-

The Little Theatre1930

-

Saffron Hill Cemetery1931

-

Braunstone Hall Junior School1932

-

Former City Police Headquarters1933

-

Savoy Cinema1937

-

Eliane Sophie Plewman1937

-

City Hall1938

-

Athena - The Odeon Cinema1938

-

The Blitz in Highfields1940

-

Freeman, Hardy and Willis - Leicester Blitz1940

-

Leicester Airport1942

-

Leicester’s Windrush Generations1948

-

Netherhall Estate1950

-

Housing at Eyres Monsell1951

-

Silver Street and The Lanes1960

-

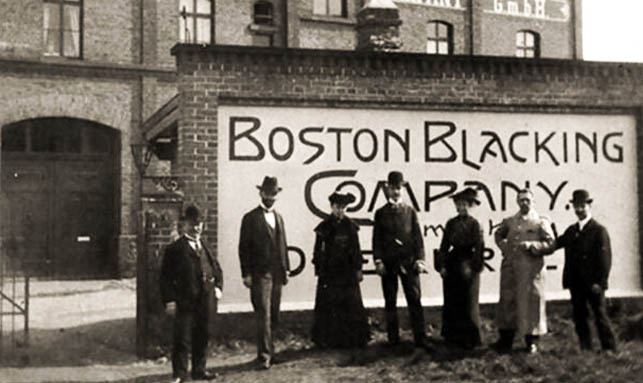

Bostik1960

-

Auto-Magic Car Park (Lee Circle)1961

-

University of Leicester Engineering Building1963

-

Sue Townsend Theatre1963

-

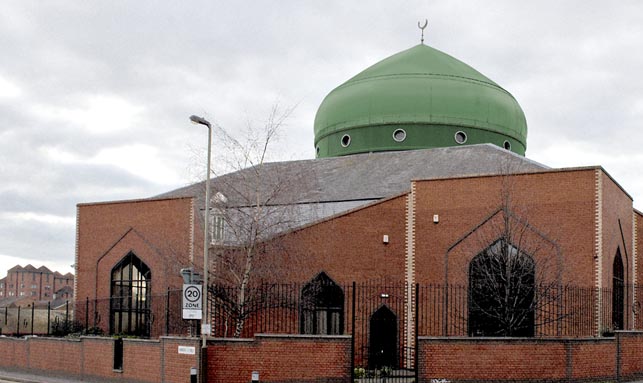

Central Mosque1968

-

Belgrave Flyover1973

Modern Leicester

(1973 – present day) Industry was still thriving in the city during the 1970s, with the work opportunities attracting many immigrants from all over the world. While industry has declined in recent years, excellent transport links have made Leicester an attractive centre for many businesses. The City now has much to be proud of including its sporting achievements and the richness of its cultural heritage and diversity.

-

Haymarket Theatre1973

-

The Golden Mile1974

-

Acting Up Against AIDS1976

-

Belgrave Neighbourhood Centre1977

-

Diwali in Leicester1983

-

Leicester Caribbean Carnival1985

-

Samworth Brothers1986

-

Jain Centre1988

-

Guru Nanak Dev Ji Gurdwara1989

-

King Power Stadium2002

-

LCB Depot2004

-

Curve2008

-

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir2011

-

Makers Yard2012

-

VJ Day 80th Anniversary2020

- Roman Leicester

- Medieval Leicester

- Tudor & Stuart Leicester

- Georgian Leicester

- Victorian Leicester

- Edwardian Leicester

- Early 20th Century Leicester

- Modern Leicester

A Place to Live